|

|

The Hermetic Fellowship Website

is optimized for viewing with the Netscape browser.

If you aren’t using Netscape, you are missing

much of the ambiance of this site (and many others on the Web)...

This page is copyright © 1999 Hermetic Fellowship.

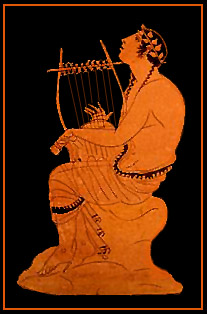

Illustration copyright © 1999 Adam P. Forrest.

Last updated on 13 November, 1999 CE.

| ORPHIC HYMN I |

Orpheus pros Mousaion· |

| The first of the 88 surviving Orphic Hymns is entitled Orpheus pros Mousaion (“Orpheus to Mousaios”), and is a general invocation of the Orphic Pantheon, in the literary form of a ritual instruction by Orpheus to his bardic son and heir Mousaios. |

|

|

|

|

The Thomas Taylor Translation (1792):

To Musaeus

| Attend Musaeus to my sacred song, | |

| And learn what rites to sacrifice belong. | |

| Jove I invoke, the earth, and solar light, | |

| The moon’s pure splendor, and the stars of night; | |

| Thee Neptune, ruler of the sea profound, | 5 |

| Dark-hair’d, whose waves begirt the solid ground; | |

| Ceres abundant, and of lovely mien, | |

| And Proserpine infernal Pluto’s queen; | |

| The huntress Dian, and bright Phoebus rays, | |

| Far-darting God, the theme of Delphic praise; | 10 |

| And Bacchus, honour’d by the heav’nly choir, | |

| And raging Mars, and Vulcan god of fire; | |

| The mighty pow’r who rose from foam to light, | |

| And Pluto potent in the realms of night; | |

| With Hebe young, and Hercules the strong, | 15 |

| And you to whom the cares of births belong: | |

| Justice and Piety august I call, | |

| And much-fam’d nymphs, and Pan the god of all. | |

| To Juno sacred, and to Mem’ry fair, | |

| And the chaste Muses I address my pray’r; | 20 |

| The various year, the Graces, and the Hours, | |

| Fair-hair’d Latona, and Dione’s pow’rs; | |

| Armed Curetes, household Gods I call, | |

| With those who spring from Jove the king of all: | |

| Th’ Idaean Gods, the angel of the skies, | 25 |

| And righteous Themis, with sagacious eyes; | |

| With ancient night, and day-light I implore, | |

| And Faith, and justice dealing right adore; | |

| Saturn and Rhea, and great Thetis too, | |

| Hid in a veil of bright celestial blue: | 30 |

| I call great Ocean, and the beauteous train | |

| Of nymphs, who dwell in chambers of the main; | |

| Atlas the strong, and ever in its prime, | |

| Vig’rous Eternity, and endless Time; | |

| The Stygian pool, and placid Gods beside, | 35 |

| And various Genii, that o’er men preside; | |

| Illustrious Providence, the noble train | |

| Of daemon forms, who fill th’ aetherial plain; | |

| Or live in air, in water, earth, or fire, | |

| Or deep beneath the solid ground retire. | 40 |

| Bacchus and Semele the friends of all, | |

| And white Leucothea of the sea I call; | |

| Palaemon bounteous, and Adrastria great, | |

| And sweet-tongu’d Victory, with success elate; | |

| Great Esculapius, skill’d to cure disease, | 45 |

| And dread Minerva, whom fierce battles please; | |

| Thunders and winds in mighty columns pent, | |

| With dreadful roaring struggling hard for vent; | |

| Attis, the mother of the pow’rs on high, | |

| And fair Adonis, never doomd to die, | 50 |

| End and beginning he is all to all, | |

| These with propitious aid I gently call; | |

| And to my holy sacrifice invite, | |

| The pow’r who reigns in deepest hell and night; | |

| I call Einodian Hecate, lovely dame, | 55 |

| Of earthly, wat’ry, and celestial frame, | |

| Sepulchral, in a saffron veil array’d, | |

| Pleas’d with dark ghosts that wander thro’ the shade; | |

| Persian, unconquerable huntress hail! | |

| The world’s key-bearer never doom’d to fall; | 60 |

| On the rough rock to wander thee delights, | |

| Leader and nurse be present to our rites; | |

| Propitious grant our just desires success, | |

| Accept our homage, and the incense bless. |

|

|

Footnotes

of Thomas Taylor

| Note 1. |

As these Hymns, though full of the most recondite antiquity, have never

yet been commented on by any one, the design of the following notes is to

elucidate, as much as possible, their concealed meaning, and evince their

agreement with the Platonic philosophy. Hence they will be wholly of the

philosophic kind: for they who desire critical and philological information

will meet with ample satisfaction in the notes of the learned Gesner, to

his excellent edition of the Orphic Remains.

|

| Note 2. | Jo. Diac. Allegor. ad Hesiodi Theog. p. 268. cites this line, upon which, and Hymn LXXI. 3. he observes, Heuriskô, ton Orphea kai tên TYCHÊN ARTEMIN prosagoreuonta, alla kai tên SELÊNÊN HEKATÊN, i.e., "I find that Orpheus calls Fortune Artemis, or Diana, and also the Moon, Hecate." |

| Note 3. | Diodorus informs us that Diana, who is to be understood by this epithet, was very much worshipped by the Persians, and that this goddess was called Persæa in his Time. See more concerning this epithet in Gyrald. Syntag. ii. p. 361. |

If you have enjoyed this site, don't forget to bookmark it

in your browser or add it to the Links at your website.

|

|

|

Return to the Hermetic Fellowship Home Page |